Jumping worms (Amynthas spp., Metaphire spp., Pheretima spp.)

Photo: Michael McTavish

Other common names: Asian jumping worms, Asian crazy worm, Alabama or Jersey jumper, Jersey wriggler, snake worm

French common name: Le ver asiatique sauteur

Order: Crassiclitellata

Suborder: Megascolecida

Family: Megascolecidae

Genera: Amynthas, Metaphire, Pheretima

Did you know? When threatened, jumping worms thrash wildly from side to side (giving them their nicknames the ‘snake worm’ or the ‘crazy worm’). If their frenzied thrashing isn’t enough to deter a predator, they can resort to breaking off segments of their tail to escape.

Introduction

The name jumping worms describes species of pheretimoid earthworms belonging to several genera including Amynthas, Metaphire, and Pheretima, which are native to East-Central Asia.

Introduced to North America in the late 1800s, they have recently begun invading natural habitats in the Northeast and Midwest, spreading primarily through horticultural trade. There is also a possibility of their introduction through sale as baitworms, however, this has not yet been documented in Canada.

These invasive worms outcompete other earthworms and their castings degrade soil quality, leaving it inhospitable to many native plant species and susceptible to increased erosion.

As they are voracious eaters, jumping worms quickly consume the top layer of organic material, making it difficult for plants to remain rooted and allowing nutrients to be washed away by rain.

Despite their wide dispersal across the United States, knowledge and research gaps concerning their biology and ecology persist. More research into traits linked to their dispersal capacity, establishment and spread is needed to counter their invasion (Amynthas agrestis (crazy worm) (cabi.org)).

General Information

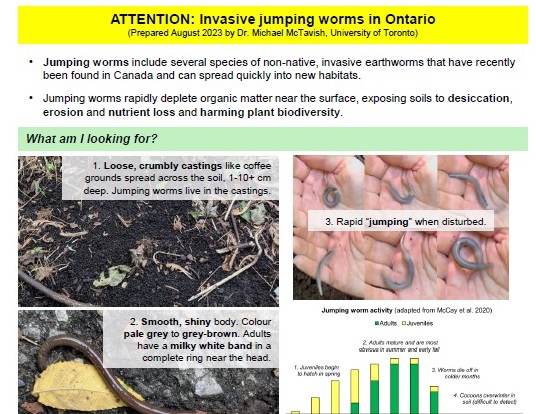

Jumping worm skin is smooth, glossy and rubbery, not slimy or squishy, to the touch. Adult jumping worms reach a length of 10-13 centimetres. When disturbed, they thrash wildly back and forth, in a motion reminiscent of a snake, and can break off tail segments to escape, earning them their nicknames ‘crazy worms’ and ‘snake worms’.

Jumping worms can be distinguished from other invasive earthworms (Lumbricus sp.) by their characteristic clitellum, a collar-like band around their bodies. The clitellum of a jumping worm is cloudy white to grey in colour and flush with their skin, located only 14-16 segments away from their head. In contrast, the clitellum of Lumbricus sp. is raised, pink in colour, and notably located more centrally along their length.

Jumping worms reproduce in an annual life cycle with some being able to do so asexually (i.e., without having to mate). This makes them particularly effective at colonizing new habitats.

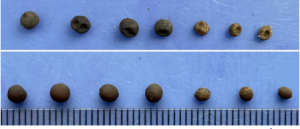

Between April and May, young jumping worms hatch from egg-filled cocoons which resemble mustard seeds. It is difficult to detect these cocoons in the soil as they blend in readily with their surroundings.

In the summer months, generally from May to August, the juvenile worms feed and grow to their adult size. The time between hatching and reproductive maturity for a jumping worm is generally only 60 days.

Between August and September, mature worms reproduce and deposit their eggs into the surrounding soil. Most adult worms die at the first freeze. Their eggs overwinter until April, protected in their drought- and cold-resistant cocoons.

Photo: Chang, C-H. et al. 2021.

Jumping worms originate from Asian grasslands, but in North America, they can be found in gardens, lawns and wooded areas living in the leaf or mulch layer of the top 7.5-10 centimetres of the soil.

Adult and developing jumping worms survive in wet, frost-free soil at temperatures between around 12-25°C (Richardson et al., 2009), however, eggs encased in cocoons are tolerant to freezing temperatures and drought.

The easiest time to spot jumping worms is between August and September when adults are at their largest. They will be present in the topsoil where they tend to appear in large numbers and will thrash wildly from side to side if disturbed.

You can also detect the presence of jumping worms through changes in the soil such as:

- Quicker than usual consumption of mulch from the topsoil.

- Changes in soil texture. Jumping worms replace the surrounding soil with their castings (waste) which resemble ground coffee.

Jumping worms can also be detected using a mustard pour, which can be performed on a patch of soil using the following steps:

- Mix 1/3 cup of ground yellow mustard seed with 4.5 litres of water

- Clear a patch of soil and slowly pour the mixture over it

- Wait for worms to move to the surface to be identified

See this factsheet from the Jumping Worm Outreach, Research, and Management Working Group for a useful guide to jumping worm identification or view this jumping worm identification guide produced by Michael McTavish at the University of Toronto.

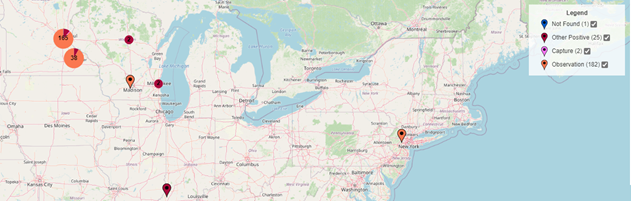

Jumping worms are native to East-Central Asia. They have been present in the United States since the late 1800s and have recently begun invading natural habitats in the Northeast and Midwest United States.

First found in Wisconsin in 2013, as of today about 17 species of jumping worms have been reported in the United States including as far west as Oregon (Asian Jumping Worms | Nebraska Extension in Lancaster County (unl.edu)). They are thought to have been introduced to North America through horticultural trade or by anglers who used them as bait.

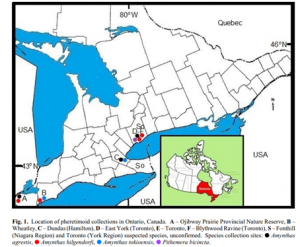

The first report of jumping worms in Canada was in 2014 on the Ojibway Prairie in Essex County, Ontario (Reynolds, J.W., 2014). In the summer of 2021, several more sightings were reported in Ontario in Wheatly, Hamilton and the Toronto region. Most jumping worm sightings were in home gardens, however, in Toronto, Ontario, jumping worms were also identified in a semi-natural ravine, demonstrating their potential to migrate from gardens into wild spaces (Reynolds and McTavish, 2021).

Ecological Impacts

Jumping worms can cause soil conditions to deteriorate substantially. They outcompete other earthworm species and feed in mass numbers in the top layer of soil, consuming organic material and replacing it with their castings.

The presence of jumping worm castings changes the soil structure, diminishing its water-holding capacity. With the organic material gone, it’s difficult for plants to remain rooted, and nutrients in the soil are readily washed away by irrigation and heavy rain. This can impact forest habitats by reducing resources for native species and may even benefit invasive plant species (Chang et al., 2021).

Jumping worms also alter the nutrient composition of the soil, making it richer in nitrogen which alters the species composition of soil bacterial and fungal communities. These changes can alter which plants are able to grow and survive, potentially leading to cascading effects on wildlife.

Jumping worms may also contribute to the release of CO2 into the atmosphere, through direct consumption and output of carbon stored in leaf litter (Chang et al., 2021).

Economic and Social Impacts

Garden soil altered by jumping worms is often inhospitable to ornamental plants, posing a threat to garden aesthetics and productivity (Johnson et al., 2021).

Jumping worms are also highly invasive in hardwood forests (Chang et al., 2021). In the United States, some states have imposed restrictions such as New York where they are a prohibited species and Wisconsin where they are a restricted species due to concerns over their potential threat to natural resources (Chang et al., 2021).

Management

Avoid Importing Jumping Worms

Preventing their introduction is the most effective method of controlling jumping worm spread into new habitats (Chang et al., 2021). This is of particular importance in Canada, where their invasion is still relatively recent (Reynolds and McTavish, 2021).

Invasive jumping worms are transported into Canada primarily through horticulture. For this reason, it’s important to avoid buying mulch, compost, nursery stocks, or potting mixes from areas with established jumping worm infestations, as these may contain egg-filled cocoons which are difficult to distinguish from the surrounding soil or debris (Chang et al., 2021). Once in the garden, worms can spread to surrounding natural areas and pose a threat to the ecosystem.

Jumping worms may also be introduced as baitworms, although this has not yet been documented in Canada. Anglers should therefore avoid buying baitworms advertised as “snake worms,” “Alabama jumpers,” or “crazy worms”. If baitworms are used, it is vital to follow all proper procedures, euthanize worms before disposal, and never dispose of unused live worms into the environment.

Report Them

Given their relatively recent spread into Ontario, early detection and rapid response (EDRR) is critical to managing the Canadian jumping worm population. Citizen science has been shown to be an effective tool in the detection, monitoring and research of jumping worms in Canada (Ziter et al., 2021; Reynolds and McTavish, 2021).

So, if you see a jumping worm, report it! Uploading a photograph along with observations will help in confirming species identity.

Kill Them

Any jumping worm discovered should be killed before being disposed of. The most humane method to euthanize jumping worms is using isopropyl alcohol, which will kill them within seconds.

Another effective method is to seal them in a clear plastic bag and leave them in direct sunlight. If you discover jumping worms in horticultural material such as soil, dispose of the contaminated material in a plastic bag, which can be left out in the sun or frozen to kill any jumping worms it may contain.

References

Amynthas agrestis (crazy worm). Invasive Species Compendium. (n.d.).

Asian jumping worm. National Invasive Species Information Center. (n.d.).

Bezrutczyk, A., Bowe, A., Brown-Lima, C., Dávalos, A., Dobson, A., Herrick, B., McCay, T., & Wickings, K. (2021). Invasive Species for Homeowners: Asian Jumping Worm. Jumping Worm Outreach, Research, and Management Working Group.

Jumping worms. Wisconsin DNR. (n.d.).

University of Nebraska. (n.d.). Asian jumping worms. Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources.