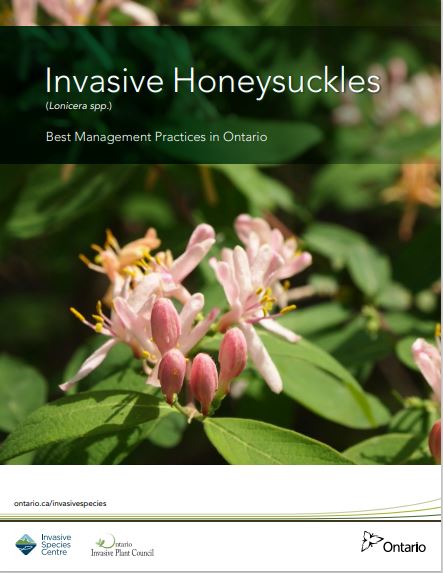

Honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.)

Invasive honeysuckle berries.

Credit: Lauren Bell

French common name: Chèvrefeuille

Genus: Lonicera

Family: Caprifoliaceae

Did you know? Out of the 16 honeysuckle species found in Ontario, 4 are considered invasive.

The amur, bells, morrow, and Tatarian honeysuckles have invaded parts of Canada since their introduction in the 1800’s. These woody shrubs were imported from Japan, Korea, China, Russia, and India for their beauty and were used primarily as ornamentals to enhance outdoor spaces. They escaped home gardens in the late 1800’s and established populations that quickly overtook natural areas. Invasive honeysuckles form dense stands that outcompete native plants for access to resources, making it for difficult for these species to grow and reproduce.

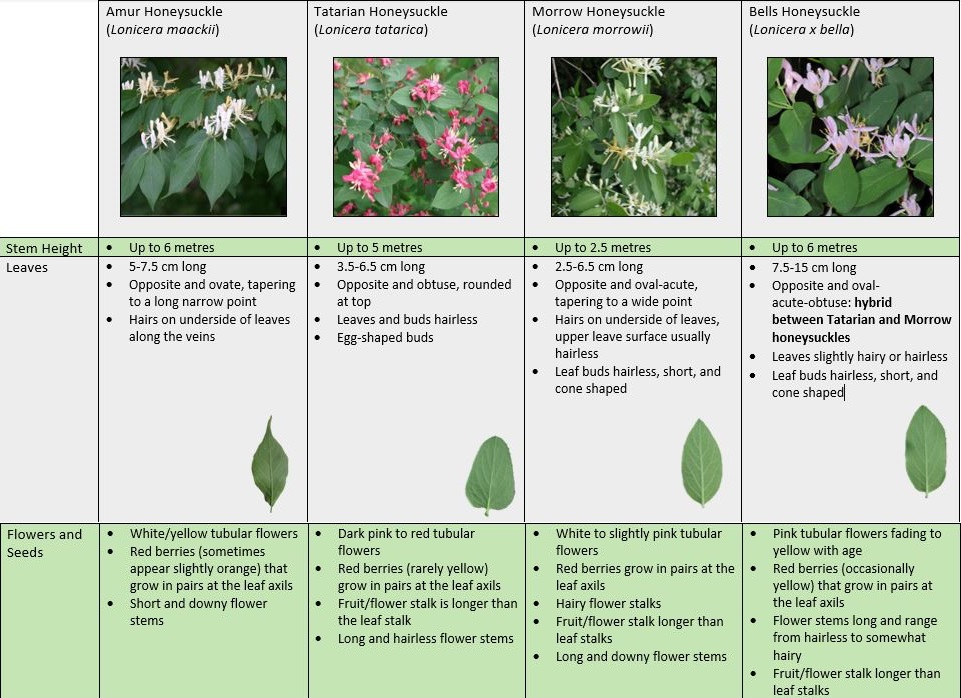

Honeysuckles are a diverse group of plants with over 180 species in the genus Lonicera throughout the Northern Hemisphere, nine of which are native to Canada. There are four common species of invasive honeysuckles that can easily be mistaken for one of their native counterparts since they tend to share similar characteristics and habitats. It’s important to learn how to tell the difference between these species to mitigate their impacts and improve prevention and management.

Invasive honeysuckles are multi-stemmed woody shrubs that form dense thickets in the areas they occupy. In general, invasive honeysuckles tend to have simple opposite leaves, big flowers, and thornless branches. See the chart under ‘Resources’ for a detailed comparison of each of the four species in Ontario.

Invasive honeysuckles can often be confused with other species, such as dog-strangling vine (invasive) or northern bush honeysuckle (native). One of the best ways to identify an invasive honeysuckle is by breaking the stem and looking at the pith. Invasive honeysuckles have hollow piths whereas native honeysuckles do not.

Invasive honeysuckles have longer growing periods than their non-native counterparts. By producing leaves earlier in the spring and retaining them longer in the fall, invasive honeysuckles can access resources (e.g., light and nutrients) over a longer period to support their growth and reproduction. They gain biomass quite quickly and eventually overcrowd and shade out nearby non-invasive understory plants.

Honeysuckle will typically begin to bloom in May or June and form berries mid-to-late summer after 3-5 years. The berries tend to remain on the plant through the winter and are eaten by birds and small mammals year-round. These animals will disperse the seeds as they move throughout the environment. Honeysuckles rely heavily on their high-seed production for reproduction and dispersal.

Invasive honeysuckles typically thrive in disturbed areas exposed to bright, natural light. In Ontario, all four invasive honeysuckles prefer similar habitats and have been known to invade urban forests, abandoned fields, pastures, floodplains, roadsides, mixed forest interiors, woodland edges, and railways.

Amur, bells, morrow, and Tatarian honeysuckles have been positively identified in over 25 American states. In Canada, these honeysuckles have been reported in Ontario, Alberta, Quebec, and the Maritimes.

Ecological Impacts

Invasive honeysuckles have a few different characteristics that allow them to outcompete native species for sunlight, nutrients, and space. These invaders leaf out early and retain leaves later, enabling them to grow bigger and form denser patches than non-invasive understory plants. Invasive honeysuckles can eventually shade out native and non-invasive plants as they grow, forming monospecific (consist of only one species) stands that reduce biodiversity. Invasive honeysuckles can also be allelopathic, meaning they produce toxic chemicals that prevent the growth of neighbouring vegetation. Non-invasive plants overwhelmed by the invader may produce less seeds over time and will therefore attract less pollinators.

Invasive honeysuckles may benefit from animals consuming their seeds, but the birds and small mammals get hardly anything in return. The seeds of invasive honeysuckles have little to no nutritional value, which does not benefit migrating or overwintering birds trying to store fat and conserve energy.

Economic Impacts

The cost of invasive honeysuckle management can be quite high depending on the population size and control method used. Management can be laborious and repetitive, which can become expensive over time. Costs can also increase if the plants growth limits the use of land for its intended purpose. For example, invasive honeysuckle growing in pastures or fields can impact the growth of crops or vegetation.

Social Impacts

Dense thickets of invasive honeysuckle can be visually unappealing and impact the aesthetic value of parks, trails, fields, gardens, and urban spaces.

Note: Honeysuckles can be a risk to human health. The berries of some honeysuckle species can be mildly poisonous to humans when consumed, producing symptoms such as nausea, rapid heartbeat, and vomiting.

General Tips

- Learn how to identify invasive honeysuckles (and how to distinguish them from non-native honeysuckles)

- Avoid planting invasive honeysuckles in gardens. Check out the Grow Me Instead guide to learn more about native plant alternatives

- Ideally, control efforts should begin early in the lifecycle before the plant starts developing fruit and seeds (before the plant reaches 3-5 years old). Older plants with berries should be targeted before the seeds are ripe and ready to be dispersed by birds and other animals (before the late-summer or early-fall). Cut off these berried branches in the summer and collect any fallen berries for disposal. Return to the plant in the fall to remove the cut stems

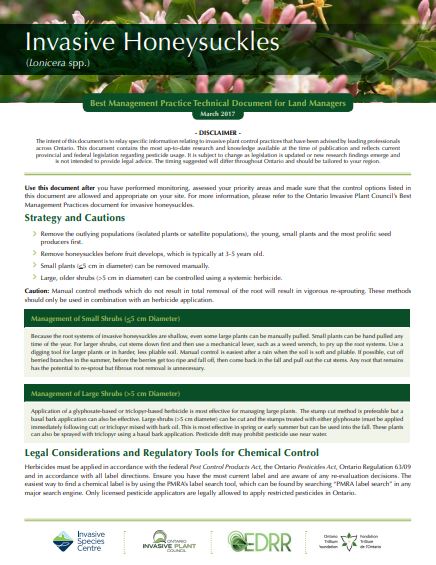

- Small plants that are 5 cm or less in diameter can be removed manually. Large, older shrubs that are more than 5 cm in diameter should be controlled using a systemic herbicide

- Target small young plants and satellite populations first before focusing on larger shrubs

Manual Control

Manual control can be useful when managing small, young populations of invasive honeysuckle. There are 5 methods of manual control: pulling, clipping, cutting, girdling, and mowing. It is important to ensure the entire root is removed when conducting manual control methods as roots left in the ground typically result in re-sprouting. As a precaution, manual control methods should be followed up with herbicide applications.

- Pulling: Small invasive honeysuckle shrubs typically have shallow roots and are easy to remove manually through hand-pulling. Honeysuckles can be pulled at any time of the year but pulling in the fall can minimize soil disruption. Digging tools, such as shovels or root wrenches, are sometimes needed to remove larger shrubs.

- Clipping: Repeated clipping of invasive honeysuckle bushes can be an effective measure of control if conducted over a long period of time (3-5 years). Avoid clipping in the winter to prevent re-sprouting in the spring.

- Cutting: Hand tools, chainsaws, or brush cutters are sometimes needed when cutting through larger stems. Sharp straight cuts are ideal when following up with chemical treatment.

- Girdling: This technique weakens larger shrubs and makes them easier to remove the following year. Herbicides must be applied to fresh stumps and girdled areas to prevent resprouting.

- Mowing: Honeysuckles can be mowed at the beginning of the season when the leaves emerge. Shrubs should be cut to within 5 cm of the ground before mowing. This technique can be repeated over time throughout the season and is most effective for smaller plants trying to re-sprout.

Disposal: Do not compost any live honeysuckles. Instead, cuttings should be placed in sealed plastic bags and left to dry in direct sunlight for 1-3 weeks. Once the roots are completely dried, cuttings can be sent to municipal composting sites and solarized limbs with berries can be sent to the landfill.

Cultural Control

Grazing and burning are two types of cultural controls that limit the regrowth of invasive honeysuckles.

Grazing: The presence of animals can sometimes impact the growth of invasive honeysuckles. For example, goats and heavy deer populations have been known to limit regrowth.

Burning: This technique is particularly useful to control invasive honeysuckle growing in open habitats. Prescribed burns can reduce the above-ground growth of honeysuckles by exhausting energy stored in the roots. Vigorous re-sprouting can sometimes occur after an initial burn, but repeated burns over the course of several years can limit re-sprouting and successfully control population sizes.

Chemical Control

The use of glyphosate-based or triclopyr-based herbicide is most effective for controlling larger plants. Consult with an expert before applying and selecting herbicide treatments.

There are two primary application methods: foliar spray and stump cutting.

Foliar spray method: This technique is typically recommended for larger thickets in open spaces where there is little risk in harming non-target species. Foliar sprays are conducted in the fall between August and October when native plants start to become dormant.

Cut-stump method: This technique is useful for controlling individual shrubs or honeysuckles growing in environmentally sensitive areas. Horizontal cuts are made at the base of shrubs as close to the ground as possible. Herbicides are immediately applied to the cut stump to kill the plant and prevent re-sprouting.

Biological Control

There are currently no biological controls for invasive honeysuckle. While many species feed on the invasive plant, most do not damage it enough to provide short- or long-term control.