Giant Knotweed (Reynoutria sachalinensis)

Photo: invasive.org

Photo: Barbara Tokarska-Guzik, University of Silesia. Bugwood.org

French common name: Renouée de Sakhaline

Additional names commonly used: Fallopia sachalinensis, Polygonum sachalinensis

Order: Polygonales

Family: Polygonaceae

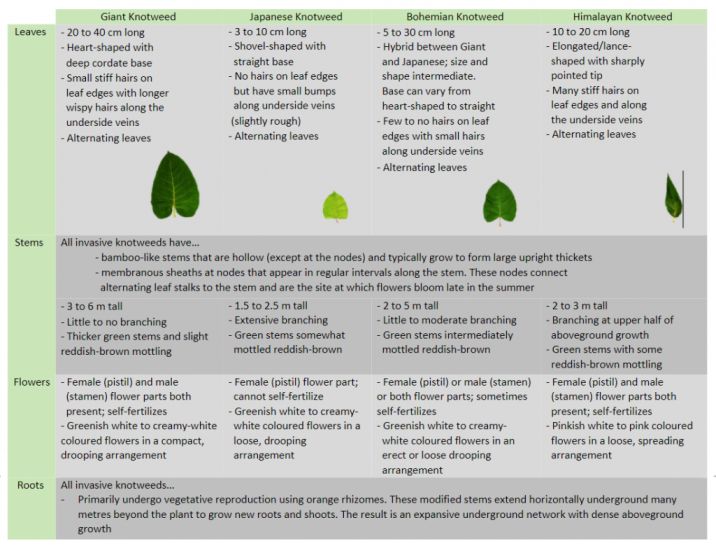

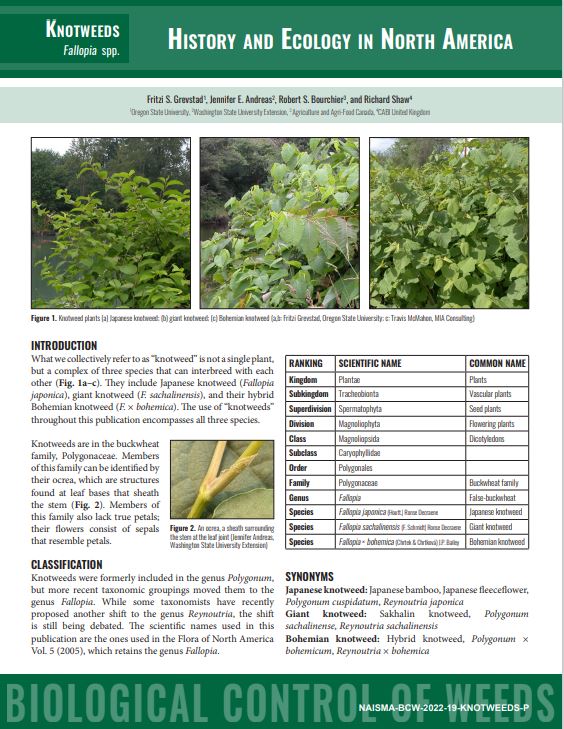

Did you know? Giant knotweed is the largest of all the knotweed species, with distinctly large, heart-shaped leaves reaching up to 40cm in length. That’s roughly the size of a standard bowling pin. The size of their leaves helps to set it apart from look-alike species, such as the smaller invasive Bohemian, Japanese and Himalayan knotweeds.

Introduction

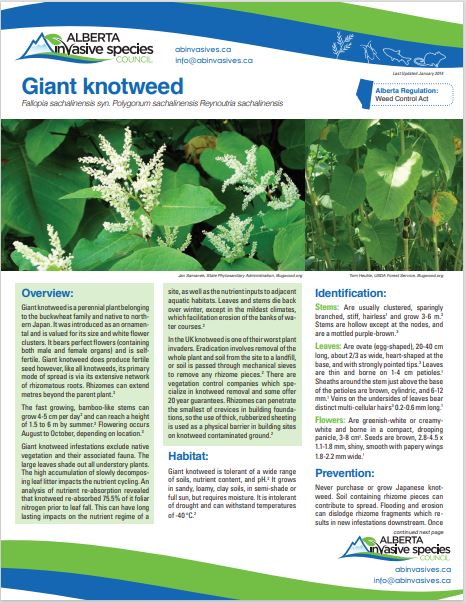

Giant knotweed is a fast-growing invasive perennial plant that is native to Asia. It was introduced intentionally into North America in the 1800’s to aesthetically enhance gardens with its impressive size and delicate flower clusters.

After its introduction, giant knotweed spread rapidly by colonizing a diverse range of habitats throughout several Canadian provinces. One of the reasons it was able to spread so quickly is because it relies heavily on rhizomes for reproduction.

Management is extremely difficult because segments of rhizome left in the soil (for example, after digging or pruning in the garden), can lead to the growth of an entirely new plant.

Knowledge on effective control measures is therefore very important when trying to eliminate giant knotweed from an area.

General Information

*Giant knotweeds can be differentiated from other species primarily based on the appearance of their leaves, overall size and branching of stems.

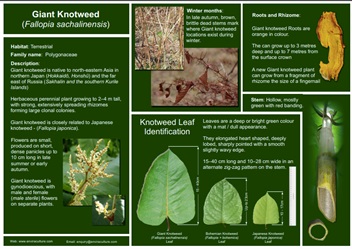

Leaves: Giant knotweed leaves can range from 20-40 cm (about 8-16 in) in length and have a deep heart-shaped base that tapers off to a tip. Their leaves also have tiny wispy hairs along the leaf margins (edges) and along the veins on their undersides. Himalayan knotweed typically has hairs on their leaves as well but are stiffer and less easily visible with the bare eye. Japanese and Bohemian knotweed, on the other hand, usually appear hairless.

Size: Giant knotweed grows the tallest and can reach 3-6 m (about 10-20 ft) in height.

Stems: Giant knotweed have little to no branching in their stems and have reddish-brown mottling. Giant knotweed (like all knotweeds) has hollow, bamboo-like stems that typically grow to form large upright thickets. They also have membranous sheaths at nodes that appear in regular intervals along the stem. These nodes connect alternating leaf stalks to the stem and are the site at which flowers bloom late in the summer.

Flowers: Their small flowers are greenish white to creamy-white in colour and grow in branched, compact clusters that can appear to be upright or drooping. While most knotweed species have similar appearing flowers, the flowers of giant knotweed commonly produces seeds (unlike the others which produce them less frequently).

Roots: Giant knotweed (like all knotweeds) primarily use rhizomes to reproduce, which form expansive underground networks that create new roots and shoots. They are orange in colour.

Reproduction in giant knotweed is primarily achieved vegetatively with rhizomes, which are horizontal underground stems that form new shoots and roots for the plant. These rhizomes can extend laterally beyond the plant (up to about 20 m/65 ft), allowing giant knotweed to rapidly extend its range and extensive network.

New pointy shoots emerge from mid-spring to late summer and grow rapidly to form tall stems with leaves. Flowers will grow and bloom late summer or early autumn. During the winter, giant knotweed loses its leaves and turns brown in colour, going dormant until temperatures warm the following spring.

While rhizomes are extremely useful for expanding the size of an individual plant, they can also be used to generate completely new giant knotweed in different locations.

If a giant knotweed is disturbed by human activity (such as pruning) or environmental conditions (such as flooding), fragments of stems or roots can be broken off. These small pieces of rhizome can get lodged in nearby soil or travel elsewhere after hitching rides on equipment or in water.

New roots and shoots can grow from a single node of rhizome and can quickly turn into new infestations.

Although giant knotweed relies more heavily on rhizomes for their rapid and aggressive growth, they can also spread-out using seeds produced by their flowers. The flowers contain both male and female parts, meaning they can self-fertilize.

Seeds appear two or three weeks after flowering and can then be transported (for example, by water, animals, or human activity) to colonize new areas.

Giant knotweed has been found growing in diverse landscapes that vary greatly in soil, nutrients, pH, moisture, and sunlight. They tend to thrive in damp areas with lots of light, such as riverbanks, shorelines, beaches, and canals. They also grow well in disturbed environments and are commonly found along roadsides.

Giant knotweed is generally considered shade-intolerant, so they are less likely to be found growing where there is less access to sun, such as in forests with dense canopy cover. If they are found to be growing in shade, it is usually because of higher moisture content in the soil.

While it is known that giant knotweed was introduced to North America in the 1800’s, it is unclear when or where it first established in Canada.

It has since been found in British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador. To report a sighting or check up-to-date distribution maps, visit EDDMapS.

Ecological Impacts

Giant knotweed grows rapidly into tall, dense monocultures that can easily outcompete native plants for limited sunlight, water, and nutrients. They can be more successful than nearby native vegetation for several reasons. For example, they have been found to release allelochemicals from their roots that then inhibit the growth of competing species in their proximity. As a result, giant knotweed threatens biodiversity by displacing native plants and the wildlife that rely on them.

Giant knotweed prefers damper soils, so it tends to grow along waterways. Its presence in these habitats can promote erosion and flooding, which can reduce water quality. This is especially problematic in riparian zones that are normally home to a large variety of plant and animal species.

Economic Impacts

Giant knotweed can grow opportunistically through small cracks in concrete and asphalt which can be costly for municipal governments if it is found damaging roads, sidewalks, and building foundations. Control efforts can be expensive since they are usually quite laborious and repetitive.

Social Impacts

Giant knotweed infestations can look unappealing when it has spread rapidly, as it makes homes, gardens, and areas in the surrounding neighbourhood look neglected.

Anglers and boaters may have a difficult time passing through dense thickets growing in waterways.

Giant knotweed that grows in residential yards can lower property values, especially if it starts damaging home foundations, fences, or driveways.

Management

Prevention is the easiest form of management for giant knotweed since its rapid and aggressive rhizome activity can make it difficult to eradicate.

Learning how to identify and report invasive giant knotweed is important when trying to manage and limits its spread.

- Learn to identify giant knotweed and how to differentiate it from other local species.

- Do not buy or plant giant knotweed

- Avoid breaking off fragments of root or stem that can establish itself in new areas.

Herbicides can be an effective control method to manage giant knotweed infestations using chemicals such as glyphosate or aminopyralid. The more commonly recommended method of application is stem injections, which targets only the invasive giant knotweed without harming native plants in its vicinity. In this case, a hole is made in each stem using a pointed tool (such as an awl) and the herbicide is injected into each stem of the plant through the holes.

Another application method is broadcast/foliar spraying. Broadcast applications are when a chemical herbicide is sprayed to cover the entire infected area, which may also impact native plants that are nearby.

Herbicides are usually thought to be most effective when applied after flowering in late summer/early autumn until the appearance of frost in winter. During this time, giant knotweed stores more nutrients in their rhizomes instead of their leaves in preparation for winter, meaning herbicides will enter the rhizomes more quickly and have a greater impact.

Stem cutting and mowing are not recommended since they risk breaking up rhizomes which can establish into new plants. For these methods to be effective, they must be done carefully, repeatedly, and in combination with herbicide use.

Stems should be cut in the summertime as close to the ground as possible, and cuttings should be bagged to dry out. After cutting back the aboveground growth, rhizomes will use nutrient stores to send up new shoots. These methods will need to be done repeatedly when new growth appears to continue depleting the plants energy reserves. Inspect and clean tools after use to ensure there are no hitchhiking plant segments waiting to invade new areas.

Avoid hand pulling or digging as it can damage the roots and cause rapid regrowth.

There is currently research being conducted on the use of biological controls (such as the introduction of insects) to manage giant knotweed, although none have been approved in Canada.