Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

French common name: Salicaire commune

Order: Myrtales

Family: Lythraceae

Did you know? Purple loosestrife has a square, woody stem.

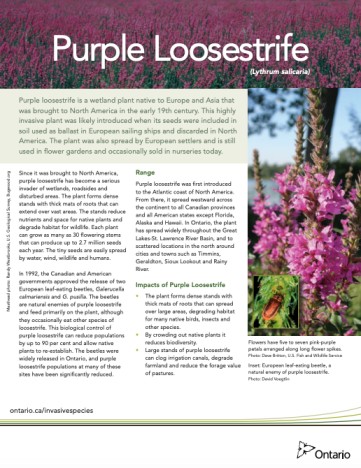

Purple loosestrife has spread rapidly across North America and is present in nearly every Canadian province and almost every U.S. state. This plant has the ability to produce as many as two million seeds in a growing season, creating dense stands of purple loosestrife that outcompete native plants for habitat. These populations result in changes to ecosystem functions, including reduced nesting sites, shelter, and food for birds, as well as an overall decline in biodiversity. The plant mass grows on average to be 60-120 cm tall and averages 1-15 flowering stems.

Purple loosestrife has evolved to tolerate the shorter growing season and colder weather of the central and northern parts of the provinces. Plants in northern regions are smaller and flower earlier than those in southern regions. These size and life cycle differences should be taken into account when identifying the plant and choosing a management option specific to your region (Purple Loosestrife BMP).

Size and shape: Plants average 1-15 flowering stems, although a single rootstock can produce 30-50 erect stems. The plant mass grows on average to be 60-120 cm tall, although some plants may grow over 2 m tall and form crowns of up to 1.5 m in diameter.

Stems: Annual stems arise from a perennating rootstock (underground organ which stores energy and nutrients in order to help the plant survive over winter and produce a new plant in spring). Stems are woody, stiff, and square-shaped, with 4-6 sides. The form of the stems is somewhat branched, smooth or finely hairy, with evenly-spaced nodes and short, slender branches. New, actively-growing shoots are green, while older stems are reddish to brown or purplish in colour.

Leaves: Leaves are simple, narrow and lance-shaped or triangular, with smooth edges and fine hairs. Leaf arrangement is opposite (two per node) or sometimes whorled (three or more per node) along an angular stem. Upper leaves and leaflets in the inflorescence are usually alternate (one per node) and smaller than the lower ones. Leaves are stalkless (attached directly to the stem), broad near the base and tapering towards the tip. Leaf size, typically 3-12 cm long, will change to maximize light availability – leaf area increases and fine hairs decrease with lower light levels. Leaves are green in summer but can turn bright red in autumn.

Flowers: Very showy, deep pink to purple (occasionally light pink, rarely white) flowers are arranged in a dense terminal spike-like flower cluster. Each flower is made up of 5-7 petals, each 7-10 mm long, surrounding a small, yellow centre. The petals appear wrinkly upon close inspection. Flowering time is climate-dependent, but in Ontario, purple loosestrife typically flowers as early as June and sometimes continuing into October (mid-June to mid-September is typical). Populations contain three floral morphs that differ in style length and anther height, a condition known as tristyly. Flowers are pollinated by insects, mostly bumblebees and honeybees, which promotes cross-pollination between floral morphs.

Roots: The strong, persistent taproot becomes woody with age and stores nutrients which provide the plant with reserves of energy for spring or stressful periods. During flood events, it can survive by producing aerenchyma – a tissue that allows roots to exchange gases while submerged in water. The uppermost portion of the root crown produces white to purple buds, some of which sprout in the spring, while others remain dormant and can become activated upon damage.

Seeds: Larger plants produce upwards of 2.7 million seeds per growing season. Seeds are produced in a tiny, rounded seedpod/capsule, 3-6 mm in length and 2 mm broad with two valves enclosed in a calyx (a cuplike structure). Each pod can contain more than one hundred light, tiny, flat, thin-walled, light brown to reddish seeds, which are shed beginning in the fall and continue throughout the winter.

Purple loosestrife was introduced to North America in the 1800s for beekeeping, as an ornamental plant, and in discarded soil used as ballast on ships. By the late 1800s, purple loosestrife had spread throughout the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada, reaching as far north and west as Manitoba. In the 1930s, it became an aggressive invasive in the floodplain pastures of the St. Lawrence River and has steadily expanded its distribution since then, posing a serious threat to native emergent vegetation in shallow-water marshes throughout Ontario. To date, this invasive plant is found in every Canadian province and every American state except Florida, Alaska, and Hawaii. Purple loosestrife can spread naturally via wind, water, birds, and wildlife and through human activities, such as in seed mixtures, contaminated soil and equipment, clothing, and footwear. Seeds may adhere to boots, outdoor equipment, vehicles, boats and even turtles.

This plant is often found near or along shorelines and can escape into new areas when seeds and viable plant material are discarded into a nearby waterway or carried off by flooding during a rain event. Road maintenance and construction create disturbed sites which can contribute to the spread of purple loosestrife. Road equipment, when not properly cleaned, can transport seeds and plant fragments to further the spread. Boats, trailers, fishing equipment, hiking shoes, and all other forms of transport vehicles can also carry the plant to new areas. Because of purple loosestrife’s ability to adapt to different climates within a short period, the chances are good that it will be very resilient to climate change, expanding its northern range as the climate warms. (Purple Loosestrife BMP)

Impacts to ecosystem function

Purple loosestrife alters decomposition rates and timing as well as nutrient cycling and pore water (water occupying the spaces between sediment particles) chemistry in wetlands. Purple loosestrife leaves decompose faster and earlier than native species (which tend to decompose over the winter and in particular in the spring). As a result, the nutrients from decomposition are flushed from wetlands faster and earlier. This change in the release timing of the chemicals produced through decomposition can slow frog tadpole development, decreasing their winter survival rate. It can also accelerate eutrophication downstream and affect detritivore consumer communities, which are adapted to spring decomposition of plant tissue. A change in nutrient cycling and a reduction in habitat and food leads ultimately to reductions in species diversity and species richness. This can lead to a reduction in pollination of native plants and as a result, decrease their seed outputs. The result is an altered food web structure and altered species composition in the area.

Impacts to species at risk, biodiversity, and wildlife

Because of its fast growth, abundant seed production, and soil changing abilities, purple loosestrife is extremely competitive. It forms thick, monoculture stands, outcompeting important native plant species for habitat and resources and therefore posing a direct threat to many species at risk. Purple loosestrife can also alter water levels, severely impacting the significant functions of wetlands such as providing breeding habitat for amphibians and other fauna. In some places, purple loosestrife stands have replaced 50% of the native species. Not only does this decrease the amount of water stored and filtered in the wetland, but thick mats of roots can extend over vast distances, resulting in a reduction in nesting sites, shelter, and food for birds, fish, and wildlife. The plant itself benefits few foraging animals, although it can be a source of nectar for bees. Where purple loosestrife is the dominant species, there is often a decline in some bird populations, such as marsh wrens. Water-loving mammals such as muskrat and beaver prefer cattail marshes over purple loosestrife.

Economic impacts to agriculture, recreation, and infrastructure

Dense purple loosestrife stands can clog irrigation canals, degrade farmland, and reduce forage value of pastures. Dense stands also reduce water flow in ditches and the thick growth of purple loosestrife can impede boat travel. This results in the decrease of the recreational use of wetlands for hunting, trapping, fishing, bird watching, and nature studies. Costs of control, habitat restoration, and economic impact of the continuously expanding purple loosestrife acreage are difficult to quantify.

Learn how to identify purple loosestrife and avoid accidentally spreading this invasive plant through recreational activities and gardening.

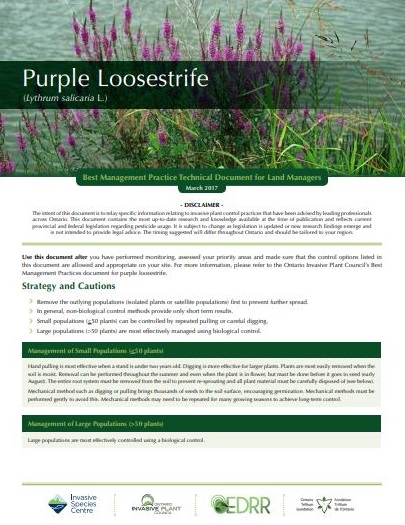

- The best time to remove purple loosestrife from your garden is in June, July, and early August, when it is in flower. Small areas can be dug by hand. Cutting the flower stalks before they go to seed ensures the seeds will not produce future plants.

- To dispose of purple loosestrife, put the plants in plastic bags, seal them, and put the bags in the garbage. Do not compost them or discard them in natural areas. Discarded flowers may produce seeds.

- Avoid using invasive plants in gardens and landscaping. Buy native or non-invasive plants from reputable retailers. See Grow Me Instead: Beautiful Non-Invasive Plants for Your Garden. Go to ontario.ca/invasivespecies, click on Here’s a list of things you can do to help fight invasive species, and click on the title.

- When hiking, prevent the spread of invasive plants by staying on trails and keeping pets on a leash.

- If you’ve seen purple loosestrife or other invasive species in the wild, please contact the toll-free Invading Species Hotline at 1-800-563-7711 or visit www.invadingspecies.com to report a sighting.

Jewelweed

Technical Bulletin

In 2017, the Early Detection & Rapid Response Network worked with leading invasive plant control professionals across Ontario to create a series of technical bulletins to help supplement the Ontario Invasive Plant Council’s Best Management Practices series. These brief documents were created to help invasive plant management professionals use the most effective control practices in their effort to control invasive plants in Ontario.

*Please note: the Invasive Plant Technical Bulletin Series is currently undergoing some updates and will be reposted when the process has been completed. Please visit the Ontario Invasive Plant Council website for updates.

Fact Sheets

Best Management Practices

These Best Management Practices (BMPs) provide guidance for managing invasive purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) in Ontario. Funding and leadership for the production of this document was provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario (CWS – Ontario). The BMPs were developed by the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (OIPC) and its partners to facilitate the invasive plant control initiatives of individuals and organizations concerned with the protection of biodiversity, agricultural lands, infrastructure, crops and natural lands

Research

Density-dependent processes in leaf beetles feeding on purple loosestrife: aggregative behaviour affecting individual growth rates

both individual and population growth rates. In two closely related chrysomelid beetles

(Galerucella calmariensis and G. pusilla) feeding on purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) …

Purple loosestrife suppresses plant species colonization far more than broad‐leaved cattail: experimental evidence with plant community implications

and cause decreases in diversity. Still invasive species are considered more deleterious to

communities than dominant natives, although evidence for this is surprisingly rare. We …

Using Sheep to Control Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

meadow in upstate New York from June to August 2008. Changes in the purple loosestrife

population and vascular plant community structure were monitored as a function of the …

The impact of exotic purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) on wetland bird abundances

have negative impacts on native plant and animal species, but this is debated. Clarifying its

influence would provide insight into appropriate management actions following invasion. We …

Current Research and Knowledge Gaps

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Further Reading

The Invasive Species Centre aims to connect stakeholders. The following information below link to resources that have been created by external organizations.