Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

Fig. 1: Tree-of-heaven. Chuck Bargeron, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org

French Common Name: Ailante glanduleux

Order: Sapindale

Family: Simaroubaceae

Did you know? Any part of the tree-of-heaven will release a foul smell when crushed. It has been nicknamed “stinking sumac” for this reason, and its odour can help you distinguish tree-of-heaven from other similar-looking native tree species.

Introduction

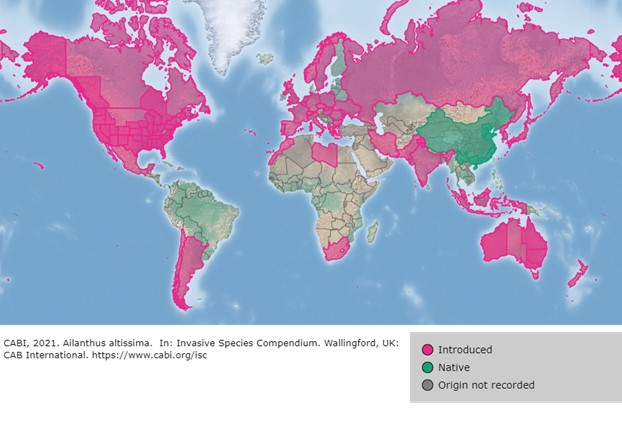

Tree-of-heaven is a fast-growing tree that is native to China and Taiwan. Now established globally, and aggressively invasive particularly in the United States and Europe, tree-of-heaven was historically brought outside of its native range for ornamental purposes.

Tree-of-heaven is believed to have the most rapid growth of any tree (native or non-native) in North America (Knapp and Cannon, 2000, as cited in Saldonja et al., 2015). The tree is capable of reproducing vegetatively. It also reproduces through primarily wind dispersal of its samaras (winged dry fruits containing seeds for germination). It has a high seed production, and the seeds have a high germination rate.

This tree is resistant to drought and tolerant of a wide range of soil conditions and pollution, which is why historically it was desirable for urban areas. Its distribution is limited by cold temperatures, and its occurrence is limited by a lack of shade tolerance.

Tree-of-heaven produces compounds that make it resistant to predations from herbivores and diseases caused by pathogens. The tree is allelopathic, meaning it releases chemicals into the soil that are toxic to other plant species.

This combination of highly successful reproductive traits, tolerance for a wide variety of environmental conditions, defense mechanisms, and allelopathy make tree-of-heaven highly invasive. This species has detrimental impacts on native plant species, built infrastructure, and human health. It is also the preferred host of the invasive spotted lanternfly.

General Information

Overall Appearance

Tree-of-heaven grows rapidly, up to 30 metres in height and 2 metres in diameter. It can be confused with tree species that are native to Canada, such as black walnut, staghorn sumac, and ash. When the leaves or twigs are crushed, they release a foul odor that can help distinguish tree-of-heaven from similar native species.

Leaves

Tree-of-heaven leaves are large (30-120 cm) and compound, meaning they are comprised of multiple leaflets, which are arranged alternately along a central stem. Examining certain features of their leaflets closely will aid in distinguishing tree-of-heaven from other similar-looking species. Tree-of-heaven leaflets have smooth (as opposed to toothed) margins, except for one or two lobes called glandular teeth at their base. There is a visually noticeable gland on the underside of these teeth.

Twigs and Bark

The twigs on a tree-of-heaven are hairless and can appear greenish, pink, reddish, or brown. Their heart-shaped leaf scars and spongy brown centers when broken are distinguishing features. The bark of young trees is thin, smooth and brownish-green, becoming thicker, rougher, and light brown to grey in colour when mature.

Flowers and Fruit

Tree-of-heaven flowers are small and pale yellow to green, growing on the tree in large clusters. Female trees produce clusters of samara fruits: single seeds encased in a papery wing. The samaras are 1-2 inches long. Note that black walnut and staghorn sumac do not have samaras.

Tree-of-heaven reproduces primarily through wind dispersal of its samaras. It has a high seed production (over 300,000 seeds annually) and the seeds have a high germination rate. The tree also reproduces vegetatively by sprouting shoots from its roots, and can even reproduce from root and stem fragments. Individuals produced in this way are clones of the parent plant and can grow in large clusters. Tree-of-heaven is a dioecious plant, meaning individual trees are either male or female.

Tree-of-heaven has been transferred and planted intentionally around the world as an ornamental plant. Seeds and roots are easily transferred unintentionally by vehicles and machinery.

In North America tree-of-heaven is generally found in urban areas where it can tolerate the poor soil and air conditions, but it can grow in a wide variety of habitats (Saldonja et al., 2015). Being intolerant of shade, it will quickly colonize disturbed areas like forest openings and edges. It has become a common (and sometimes even dominant) component of forest vegetation in parts of the U.S., having been found in hemlock, oak-hickory, and maple-birch forests (Saldonja et al., 2015). Corridors, like roadsides, railways, and riverbanks, can help facilitate tree-of-heaven’s spread. This tree’s ability to establish under poor environmental conditions (like drought and pollution) that many native plants would not tolerate contributes to its invasiveness.

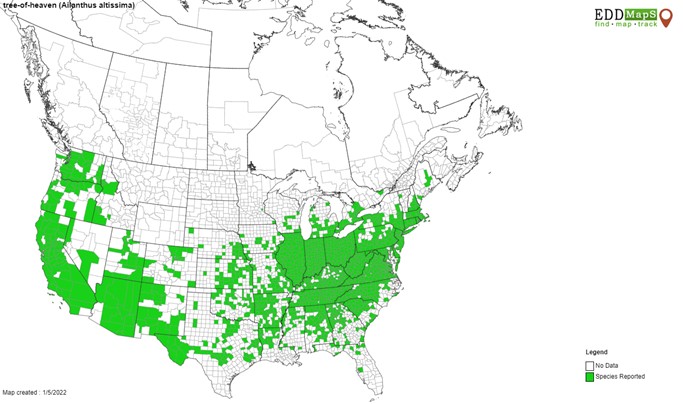

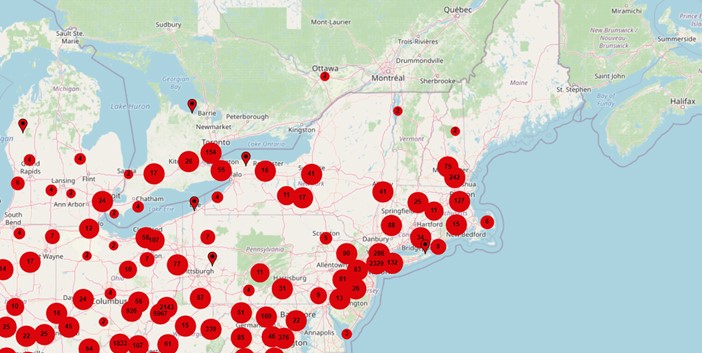

Native to northeast and central China and Taiwan, tree-of-heaven was introduced to North America in 1784 near Philadelphia (Jackson and Wurzbacher, 2020). It was introduced again to New York in 1820 and to California in the 1850s (Fryer, 2010). Tree-of-heaven became available in nurseries by 1840 and was planted in urban areas, having been considered desirable as a hardy ornamental plant (Jackson and Wurzbacher, 2020). It is now widespread in the United States. In Canada, tree-of-heaven has been found in British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2021). Although its distribution is limited by cold temperatures (occurring from 22o to 34o N in latitude), it has been documented on every continent except Antarctica (Udvardy, 1998, as cited in Cornell Cooperative Extension, 2019).

Ecological Impacts

Once tree-of-heaven has colonized a natural area, it can displace native plants, altering the surrounding plant community (Saldonja et al., 2015). Tree-of-heaven does this through outcompeting surrounding plants for water, sunlight, space for roots, and nutrients, and through allelopathy, meaning it releases toxins into the soil that inhibit other plants’ growth. A shade-intolerant plant, tree-of-heaven particularly impacts early-successional environments, where there is full sunlight. As a result, it can completely alter the trajectory of ecological succession (the shifting species composition of plant communities, as soil chemistry, amount of sunlight, and other conditions change over time after a disturbance such as logging) in that area.

Tree-of-heaven is also the preferred plant host for spotted lanternfly, a destructive invasive pest that will cause significant harm to grape vines, tender fruit trees, and forests if it establishes in Canada. Spotted lanternfly is a nuisance in urban areas as well, as it swarms trees in large numbers and secretes a sticky substance.

Economic and Social Impacts

In urban areas where tree-of-heaven has often been planted, it can be detrimental to the urban landscape and to human health. The tree’s roots break up asphalt and crack through walls and building foundations, and it can also enter sewers (Saldonja et al., 2015). It is costly and difficult to eradicate.

Tree-of-heaven’s pollen causes allergies (Kowarik and Saumel, 2007, as cited in Saldonja et al., 2015) and its sap causes dermatitis and very rarely, myocarditis if it enters the bloodstream (Bisognano et al., 2005, as cited in Saldonja et al., 2015). The tree also has an unpleasant odour.

In its native range in Asia, different components of the tree-of-heaven have been historically used in folk medicine. With antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, tree-of-heaven may have modern medicinal potential as well (Fryer, 2010). In China the tree is important for timber and fuelwood (Fryer, 2010).

Tree-of-heaven has been used in its invasive range for restoration of disturbed, toxic sites, since it has much higher tolerance for pollutants like mercury and sulfur, saline soils, and low pH than most native species (Fryer, 2010). However, given its extremely invasive properties it is usually best avoided even for ecological restoration purposes.

Management

Prevention and Reporting

To help prevent the spread of any invasive plants, remove plant debris and soil from your vehicle and machinery after visiting infested sites. Follow workplace guidelines if applicable.

As tree-of-heaven is aggressively invasive and a preferred host for spotted lanternfly, do not choose this tree as an ornamental for your yard. Consider seeking a professional to remove any tree-of-heaven from your property. If for any reason removal is not viable, continue to monitor your tree-of-heaven for spotted lanternfly.

If you think you’ve found tree-of-heaven (or spotted lanternfly), please report your sighting to EDDMapS. You can also enter it on iNaturalist or email info@invasivespeciescentre.ca.

Control

Controlling tree-of-heaven requires a persistent regimen of chemical treatments, as its ability to reproduce from stumps and root fragments renders eradication from mechanical methods nearly impossible. Herbicides need to be applied late in the growing season, when they will be taken up by the tree as it is moving carbohydrates to its roots. Stands of tree-of-heaven will require ongoing monitoring for regrowth and repeated applications for successful eradication.

Herbicides with triclopyr or glyphosate are recommended for practitioners treating tree-of-heaven, as they are not active in the soil and therefore will likely not be taken up by non-target plant species. There are a few different techniques for herbicide application:

- Foliar – herbicide is sprayed on the leaves. To control dense growth, this treatment will be followed up with basal bark or hack-and-squirt applications (see below).

- Basal bark – herbicide is applied all around the base of the tree from the ground up to 30-45 cm.

- Hack-and-squirt – herbicide is applied to angled cuts in the tree.

If a single tree needs to be cut down for safety reasons, it should be treated with the above techniques, left for thirty days, and then cut after it dies. Simply cutting the tree and then applying herbicide to the stump will not prevent root suckering (new stem growth from the roots).

Currently, a strain of the fungus Verticillium nonalfalfae that is specific to tree-of-heaven is being studied for its biocontrol potential. Verticillium wilt in tree-of-heaven caused by this fungus has been documented in Pennsylvania and Ohio (Rebbeck et al., 2013). This disease causes leaf discolouration and dieback and can eventually kill the tree.

While spotted lanternflies can kill tree-of-heaven individuals through their feeding habits and excretions, they do not kill these trees on a larger scale. They are also not desirable agents of biocontrol as invasive pests themselves.

References

Cornell Cooperative Extension. (2019). Tree of Heaven Background and Distribution. Available: https://moodle.cce.cornell.edu/mod/page/view.php?id=12562

Fryer, Janet L. (2010). Ailanthus altissima. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/ailalt/all.html

Jackson, D. R., and Wurzbacher, S. (2020). Tree-of-heaven. PennState Extension. Available: https://extension.psu.edu/tree-of-heaven

Rebbeck, J., Malone, M. A., Short, D., Kasson, M. T., O’Neal, E. S., & Davis, D. D. (2013). First Report of Verticillium Wilt Caused by Verticillium nonalfalfae on Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) in Ohio. Plant disease, 97(7), 999. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-01-13-0062-PDN

Sladonja, B., Sušek, M., & Guillermic, J. (2015). Review on Invasive Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle) Conflicting Values: Assessment of Its Ecosystem Services and Potential Biological Threat. Environmental Management, 56(4), 1009–1034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0546-5

Resources

Ailanthus altissima (fs.fed.us)

Ailanthus altissima (tree-of-heaven) (cabi.org) Controlling Tree of Heaven: Why it Matters (psu.edu)

Spotted Lanternfly – Profile and Resources | Invasive Species Centre

TOH: Tree of Heaven Identification, Look-a-Likes, and Biology (cornell.edu)

Tree-of-heaven – Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle – Canadian Food Inspection Agency (canada.ca)

tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) – EDDMapS State Distribution – EDDMapS