Red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans)

Basking red-eared slider. Photo: Joy Viola, Northeastern University; Bugwood.org

French Common Name: Tortue de Floride

Order: Testudines

Suborder: Cryptodira

Superfamily: Testudinoidea

Family: Emydidae

Did you know? Similar to American alligators, the sex of red-eared sliders is determined by the temperature they experience during development. Hatchlings that developed under higher temperatures will be female, while those who developed under lower temperatures will be male.

Introduction

Red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) are an invasive turtle species to Canada, originating from the Mississippi River waterways of the United States. A world traveler, this turtle species has introduced populations on every continent except Antarctica. Due to their popularity as pets in many parts of the world, their primary mode of introduction is through pet release. Though small as juveniles, the turtles grow into large adults with complex needs which pet owners may fail to foresee, leading to their unfortunate, and often illegal, release into the wild. Their high fecundity and adaptability to new habitats make them effective competitors over native turtles and they are capable of spreading diseases, such as ranavirus, to other wildlife. Red-eared sliders may be mistaken for native species like Western painted turtles but can be distinguished by the red markings on their head. Proper identification of either turtle can be an effective means of protecting natural ecosystems.

General Information

Adult red-eared sliders are medium-sized (12.5 to 29 cm in length), freshwater turtles with distinctive red patches on either side of their head. Both their carapace (shell) and skin are olive to brown in colour with yellow or green stripes running down their neck, legs, and tail. Females are usually larger than males, while males have thicker and longer tails. The bottom of their shell is pale yellow with two rows of dark blotches. The top of their shell has a ridge down the middle. Red-eared sliders may be mistaken for the Western painted turtle, who have similar markings but lack the unmistakable red patches. For a detailed visual guide, see BC Turtle Watch’s identification guide.

Red-eared slider eggs are white, oval and 31-43 mm long, weighing between 6.1 to 15.4 grams. Hatchlings are born with the appearance of small adults.

Red-eared slider courtship and mating activities usually occur in the spring and summer months and take place in the water. Nesting follows, in the spring and summer when female turtles dig holes in the soil to deposit their eggs. A single female turtle can lay up to four clutches each year and each clutch will contain between four and twenty-three soft-shelled eggs. Hatchling emergence is weather dependent, requiring a range of temperatures between 22°C to 30°C for 55 to 80 days. For some populations, the hatchlings emerge from the nests in the late summer, while in others they overwinter in the nest. The new hatchlings are independent and like small adults in appearance. Sexual maturity is based on size, not age, with females reaching reproductive maturity at a plastron (lower half of the shell) length of 16–17 cm (Zhang et al., 2020). This usually occurs at around four years of age. Their high fecundity in comparison to native turtles allows them to be a competitive invader. Those that reach adulthood have an average lifespan of 25 years and can live up to 40 years.

Red-eared sliders are a temperature-dependent sex determination (TDS) species, much like American alligators. This means that the sex of the turtle at birth will be dependent on the temperature it experienced during development. Higher temperatures during development (around 31°C) will produce female offspring, while lower temperatures (around 26°C) will produce male offspring. It is believed that this occurs because higher temperatures increase the expression of aromatase, an enzyme that affects sex determination through irreversibly catalyzing androgens into estrogen, producing female turtles (Matsumoto et al., 2013).

Red-eared sliders are an aquatic species and rarely spend time on land. They inhabit a variety of freshwater habitats, including rivers, swamps and ponds and can often be seen basking on branches or rocks which extend out of the water.

Though they prefer quiet, freshwater habitats, they are a highly adaptable species capable of tolerating brackish waters, manmade canals, and city ponds. They may also wander far from the water, allowing them to quickly find and colonize newly available habitats.

Adults are omnivorous, feeding on plants and small animals such as fish, worms, tadpoles, and aquatic insects, but tend to be more herbivorous as juveniles.

The easiest way to identify a red-eared slider is from the distinctive red patches on either side of their head.

These turtles spend most of their time basking on anything which protrudes from their freshwater habitats, such as logs or larger rocks. Urban environments with higher population densities are more likely to experience an infestation of the turtles because of higher rates of pet ownership and subsequently, release.

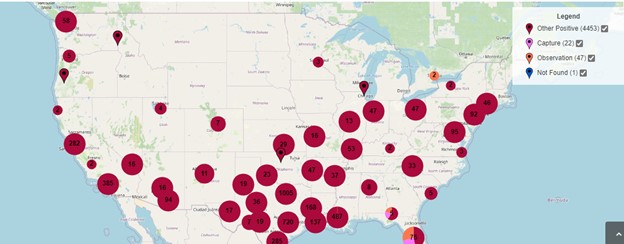

The red-eared slider is native to the Mississippi River waterways in the United States and has been reported in 32 states outside of its native range.

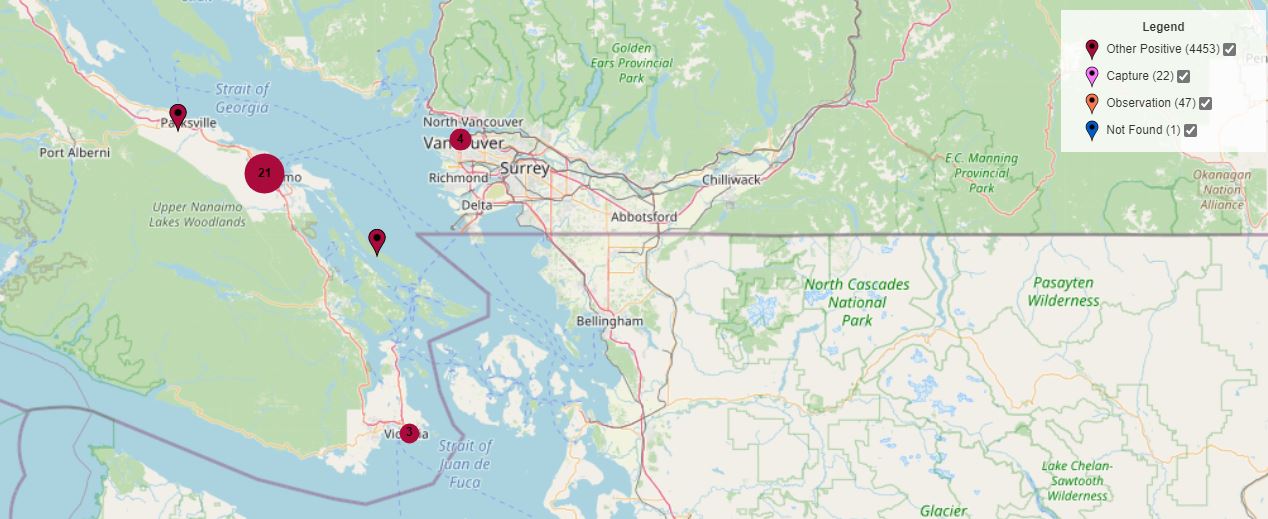

In Canada, red-eared sliders have been sighted in Southern Ontario and British Columbia. In British Columbia, populations are found on Vancouver Island from Victoria to Courtenay and on the South Coast of the province, including in Metro Vancouver, as well as in the Southern Interior.

Globally, the red-eared slider has been introduced to every continent except Antarctica and is invasive to several countries including South Africa, Australia, South Korea, Thailand, Austria, Latvia, Canada, and the United States to name a few. A complete list of countries with introduced populations can be found by viewing their distribution table provided by the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI).

Red-eared sliders’ primary vector of spread and distribution is via the pet and aquaculture trade. Owners may not recognize the size that red-eared sliders can become in their enclosures or the length of time that they may survive. Initial introduction can be associated to urban centres, but red-eared sliders may also not be widely reported because of their similarity to Western painted turtles. It’s imperative that if you own a red-eared slider, that you don’t let it loose and contribute to their spread.

Ecological Impacts

Red-eared sliders compete with native turtles for food and habitat and may transmit diseases such as Salmonella, respiratory disease or ranavirus. Ranaviruses pose a threat to wildlife including amphibians, reptiles and fish and native Ontario turtles such as the Snapping Turtle. Larger than native species such as the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii), red-eared sliders also outcompete other turtles for basking space on logs and rocks. Native turtles need this access to warm sunshine to maintain healthy digestion and metabolic rate. With 7 out of the 8 native turtle species considered at risk by the Canadian government, the additional threat of non-native competitors is of vital concern.

Several native species in Canada are considered threatened by the red-eared slider. Some examples include the Western painted turtle (COSEWIC, 2006) which is considered threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and the Spiny Softshell (OMECP, 2020b) and Spotted Turtle (OMECP, 2020c) which are classified as endangered under the endangered species act and Blanding’s Turtle which is classified as a threatened species under the same act (OMECP, 2020a). Native turtles already experience a number of challenges related to habitat destruction, road mortality, and the threat of predators, and the addition of another species could further compound these already arduous barriers to survival.

Economic and Social Impacts

Domestic red-eared sliders are carriers of Salmonella, bacteria that can be harmful to humans. The bacteria found in their droppings can be easily spread to their bodies where humans may touch them during handling. Contact with pet red-eared sliders has been linked with at least one outbreak of Salmonella in the United States.

Any invasive species can cause economic and social challenges for communities including elevated management costs, infrastructural damage, or ecological alterations leading to the decreased ability to participate in recreational activities, to name a few. While red-eared sliders are not known to cause many threats external to ecological harm, this disruption can still pose changes in fragile systems and unexpected costs.

Management

Regulations

It is prohibited under Canadian federal Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations made under the Fisheries Act, to release any aquatic species into a region or body of water where it is not indigenous. These regulations help to protect Canada’s waterbodies from the spread of invasive aquatic species and prohibit actions which could lead to their introduction and spread including transportation, release and introduction.

Pet Release

Putting a stop to pet release is the most effective way to protect native species and habitats from invasive red-eared sliders. Pet owners should consider the following.

Reflect before you buy

- Plan to care for your pet long-term – Although baby turtles can seem like cute, easy pets, it’s important to remember that these are living creatures that will grow into adults with complex needs and can live up to 40 years.

- Adopt, don’t shop – Surrendered turtles need new homes. If you are committed to caring for a red-slider long-term, consider adopting one

Alternatives to release:

- Contact the retailer for advice, or for a possible return/surrender of your pet.

- Give it to another aquarium or pond owner. You can research groups on social media, or on online platforms, and inquire whether they’d be interested in owning your pet.

- Donate it to a local aquarium society or school if they are interested in studying or having it for learning purposes.

Don’t:

- Never release unwanted pets into the environment. – Red-eared sliders are not native to Canada and released pets have the potential to disrupt the environment and cause harm to wildlife.

What to do if you spot a red-eared slider in the wild

Detection and rapid response are other important steps in the management of invasive species. Reporting a sighting is a great way to understand and mitigate invasive red-eared slider populations in your area.

Red-eared slider sightings in British Columbia can be reported to the Invasive Species Council of BC here. Sightings of red-eared sliders across Canada can be reported through EDDMapS.

References

Colorado Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (2018). Species account for the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans). Compiled by Lauren Livo. From http://www.coparc.org/red_eared_slider.html

COSEWIC (2016). COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Western Painted Turtle Chrysemys picta bellii, Pacific Coast population, Intermountain – Rocky Mountain population and Prairie/Western Boreal – Canadian Shield population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xxi + 95 pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry website).

http://www.naturemappingfoundation.org/natmap/facts/red-eared_slider_712.html

https://bcinvasives.ca/invasives/red-eared-slider/

https://ontarionature.org/ranavirus/

https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/species/slider/

https://www.catalogueoflife.org/?taxonKey=5F8HQ

Matsumoto, Y., Buemio, A., Chu, R., Vafaee, M., Crews, D. (2013). Epigenetic control of gonadal aromatase (CYP19A1) in temperature-dependent sex determination of red-eared slider turtles. PLoS ONE, 8(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063599

(OMECP) Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (2020a). Blanding’s Turtle Government Response Statement. From https://www.ontario.ca/page/blandings-turtle-government-response-statement

(OMECP) Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (2020b). Spiny Softshell government response statement. From https://www.ontario.ca/page/spiny-softshell-government-response-statement

(OMECP) Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (2020c). Spotted Turtle government response statement. From https://www.ontario.ca/page/spotted-turtle-government-response-statement

Zhang, Y., Song, T., Jin, Q. et al. (2020). Status of an alien turtle in city park waters and its potential threats to local biodiversity: the red-eared slider in Beijing. Urban Ecosyst 23, 147–157 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-019-00897-z