Water Ferns (Azolla spp.)

Azolla covering a freshwater swamp area

Courtesy of the Electronic Atlas of the Flora of British Columbia

Common Names: Waterferns, water ferns, waterfern, mosquito fern, mosquitofern, crested mosquitofern, Carolina mosquitofern, eastern mosquitofern, feathered mosquitofern, water velvet, Mexican mosquito fern, large mosquito fern

Latin Name: Genus Azolla;

Species: Azolla caroliniana, Azolla cristata, Azolla filiculoides, Azolla mexicana, Azolla pinnata, Azolla microphylla

French Common Name: Fougère D’eau

Order: Salviniales

Family: Salviniaceae

Did you know? There are six species within the genus Azolla that are extinct.

Introduction

Azolla is a group of aquatic plants, with three identified species: Azolla filiculoides, Azolla cristata, and Azolla pinnata. These species are native to North America, South America, Africa, and Asia, but have spread outside their home ranges to parts of Asia, Africa, Europe, Oceania, North America, and Central America. In 2018, Azolla cristata populations were recorded in Ontario within Leeds and Grenville County, as a possible invasion (Brunton & Bickerton, 2018). Biologists argue over Azolla’s native range in Canada, but A. filiculoides is distributed throughout the United States, mainly in the rocky mountain states, and up into South and Central British Columbia. Non-native Azolla’s close proximity to Canada threatens the invasion of this aquatic plant. Once introduced, Azolla poses a significant threat to native Canadian plants and ecosystems. Its main threat is outcompeting native species for resources and making aquatic habitats uninhabitable for native flora and fauna. This plant is known to especially negatively effect native wild rice populations, which in turn threatens the Indigenous significance and resources of the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Its main system of distribution is through contaminated watercraft and aquatic equipment, shorebird and waterfowl undergoing migration, and the aquarium and pond trade. Those interested in aquatic plants should be cognizant of the various invasive versions of Azolla when purchasing a species – or consider buying native species instead.

There are several debates over the taxonomy of the species, and many believe some species are the same, which is evidenced by all the species having similar traits. Taxonomists have recently declared only two distinct species exist within the genus in America: Azolla cristata and Azolla filiculoides (Evrard & Van Hove, 2004), while another species, Azolla pinnata, is native to Africa and Asia.

Description

Azolla species look very similar. All species grow on the water’s surface and can form a dense mat-like covering on the surface.

Also Known As

Description

Photo

Azolla cristata

Carolina mosquitofern

Carolina azolla

Water velvet

Leaves are 5-10mm long, bright green in colour but can turn red or rust colour in winter or in bright environments. The leaves overlap and are scale-like in appearance.

Trichomes are present on the upper surface of the leaves, giving it a velvety appearance. The roots are wispy and dangle beneath it into the water.

Azolla filiculoide

Azolla microphylla

Azolla caroliniana

Water fern

Large mosquito fern

The plant rarely grows more than 25mm long. The small green leaves are alternately arranged along the stem. The leaves overlap and are scale-like in appearance. Trichomes are present on the upper surface of the leaves, giving it a velvety appearance. Roots hang beneath the plant into the water.

Azolla pinnata

Mosquito fern

Feathered mosquito-fern

The plant grows to be 1.5-2.5cm long. The leaves grow in a feather-like formation, branching off from the main stem located along the middle axis of the plant. Leaves are 1-2mm long, and can be green, brown, or reddish in colour, typically discolouring to brown or red near the base of the plant. Roots run laterally beneath the plant and have a feathery appearance when submerged.

Roots that grow 40-50mm beneath the water’s surface will drop off.

Currently, the only way to decipher Azolla cristata and Azolla filiculoides is microscopically through their trichomes. Trichomes are small, hair-like projections on the upper surfaces of the leaves. Azolla filiculoides has unicellular trichomes and Azolla cristata has two-celled trichomes.

General Information

Azolla is capable of growing its population at a rate that doubles its size within 4-5 days in optimal conditions. It does this mainly through vegetative reproduction, where a fragment of plant will break off and grow as a separate plant. This pathway to easy propagation must be considered when managing Azolla populations. Fragments of plants can easily be distributed by currents, aquatic equipment, such as boats, as well as swimmers and local fauna. Vegetative reproduction is one of the reasons Azolla spreads so easily. Azolla is also capable of sexual reproduction in optimal conditions, where spores will be released into the water.

A. filiculoides and A. pinnata are able to overwinter in humid and more temperate conditions, but A. cristata is able to withstand winter water temperatures of 5°C. A cristata’s optimal summer water temperature is between 25-30°C.

Azolla favours humid, warm conditions in freshwater. A. filiculoides favours tropical conditions with humid summers and mild winters. All species of Azolla do best in slow moving or still waters, such as streams, rivers, lakes, and ponds, but have also been found in man-made waterways such as ditches and dams. A. pinnata has been observed in cattle paddocks and farm ponds due to Azolla thriving in nutrient-rich waters. A. pinnata has also been observed growing on moist soils around rivers, ditches, and ponds. This observation leads to the belief that Azolla populations may be able to survive periods of low water levels and drought.

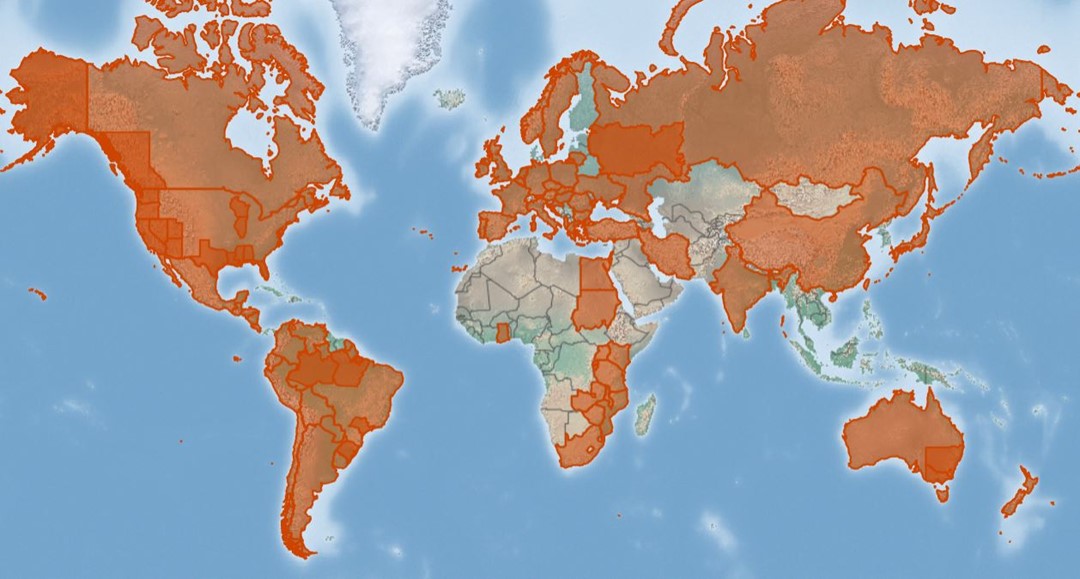

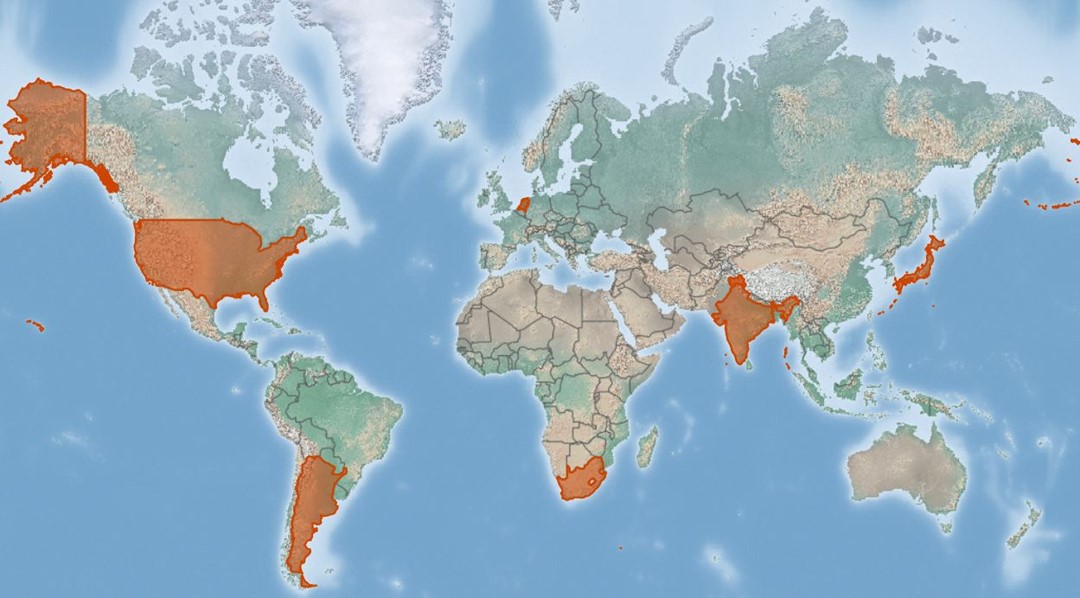

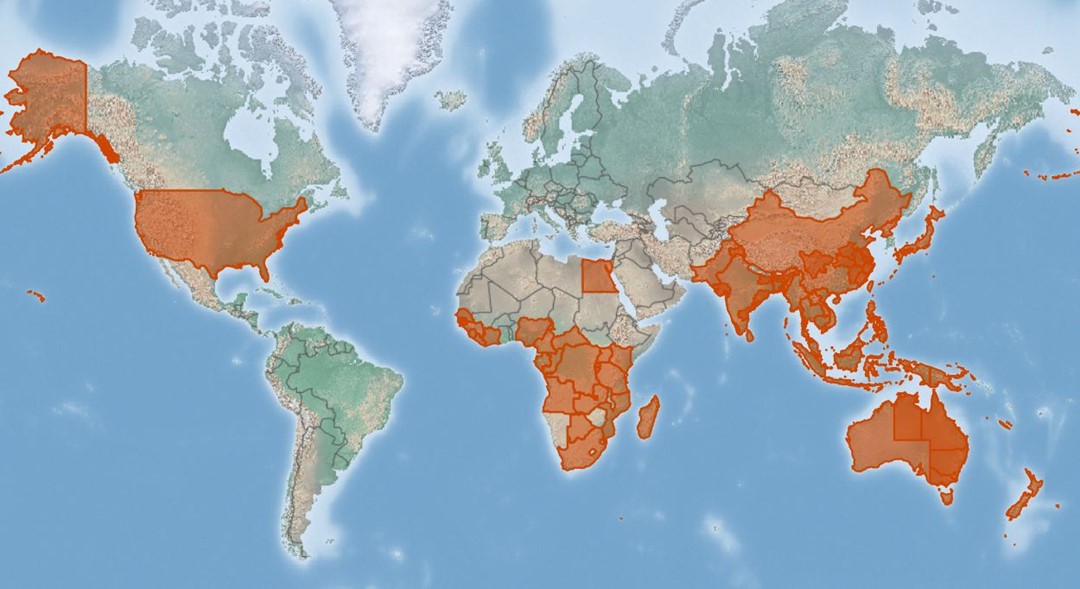

Azolla is found globally, but each species has their own native and invasive distributions.

A. filiculoides is native to South America, most of Central America and up through western North America. It has been introduced to Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, the Caribbean and Hawaii.

A. cristata is native to the eastern United States, where it coined the name Carolina mosquitofern and Carolina azolla. Biologists debate over its native range spanning into Canada, but most observations of this plant in Ontario are considered invasive (Brunton & Bickerton, 2018). A. cristata has been introduced to parts of Africa, Asia, and Europe, and is considered invasive in Africa and Asia. There is also a population of A. cristata in Argentina, but it is debated whether or not this population is native or introduced.

A. pinnata has native ranges in Africa, Asia, and Australia. The plant has been introduced to the United States and New Zealand, and is considered invasive in New Zealand.

Azolla has been distributed globally through commercial trade as an aquarium and ornamental plant. It has also been introduced intentionally to decrease mosquito populations, as the plant covers the water’s surface and decreases the area in which mosquitos can lay eggs. However, this intentional distribution has backfired due to Azolla inhibiting the growth of native plants, leading to catastrophic changes in ecosystem function and decrease in native flora and fauna presence.

Azolla can also be distributed through hitchhiking on boats, swimmers, and animals in an aquatic habitat. Fragments of Azolla can break off and stick to people, equipment, and even animals, which in turn can travel to other aquatic ecosystems and be placed wherever the fragment comes into contact with water. This is a common mode of distribution for invasive aquatic plants, and therefore it is important to clean, drain, and dry your boats after exiting a waterbody, as to not transfer numerous invasive or pest species from region to region. It’s also important to remember: Don’t Let It Loose!

Ecological Impacts:

Azolla grows over the water’s surface in a large mat-like structure. These mats can grow to take up several hectares and can span several kilometers at a time. The covering of the water’s surface blocks sunlight to any organisms below. The native aquatic flora that depends on sunlight will die off, causing a chain of events that will negatively affect the native fauna that rely on plants to survive. These ecosystem changes also cause the waterbody to become low in oxygen, which can cause further decrease in native flora and fauna. These changes are often irreversible or would cost a great amount of energy and money to restore the ecosystem. Aquatic ecosystem changes can also lead to detrimental changes in nearby habitats, having a lasting effect on the entire area.

Social and Economic Impacts:

Azolla patches have the potential to become jammed in boat motors, intwined with swimmers, and can have other negative effects on the general recreational use of a waterbody. The density of Azolla also has the potential to clog irrigation channels, in turn causing flooding and drought in some areas. Azolla has historically caused detrimental impacts on wild rice populations, which has consequences on the aquacultural cultivation of wild rice, but also to the significance of wild rice to Indigenous peoples. Due to its destruction, it would be incredibly costly to restore ecosystems impacted by Azolla. The cost to restore ecosystems once overtaken by Azolla far outweighs the cost of preventing its introduction.

The Ontario government has deemed Azolla to be restricted under the Invasive Species Act as of January 1st, 2024 (New invasive species proposed for regulation under the Invasive Species Act | ontario.ca). Restricted species are illegal to be deposited or released in Ontario and cannot be brought into any park or conservation reserve.

The prevention of species introduction is much easier and more cost-effective than controlling a species once it is established. Thus, it is of high importance that Azolla is not introduced to more areas within Canada, as it poses a significant risk to Canada’s native species and would cause significant economic impacts for its removal and management.

In South Africa in 1997, the biological control of Azolla filiculoides was undertaken by the release of the weevil, Stenopelmus rufinasus, to feed on the invasive plant. This control program was incredibly successful in destroying invasive Azolla populations within just a few years, but concern was raised about the weevils resorting to eating the native A. pinnata once the invasive A. filiculoides populations were irradicated.

Azolla is susceptible to the chemical control agents of glyphosate, paraquat, and diquat, however, some of these chemicals are either banned or have known damaging impacts on ecosystems. It is therefore recommended that preventative measures of Azolla introduction be priority in the management of this plant.

Azolla plants are typically small and difficult to spot in their initial stages of growth and spread. Therefore, the initial signs of Azolla spread may be difficult to observe, however, when cleaning, draining and drying your boats, be on the look-out for plants that may look like Azolla or fragments of Azolla.

Once established, Azolla can grow and double its population in just a few days. The initial signs and symptoms of Azolla taking over an ecosystem is the death of native flora and fauna. Due to the mat-like growth of Azolla on the water’s surface, it will block out sunlight to native plants below, and causes an ecosystem with low levels of oxygen. These ecosystem changes can lead to decrease in native species in a short period of time. It is therefore important to monitor the health and growth of your nearby ecosystems.

Ontario considers Azolla to be a restricted plant within the province. The Canadian Coalition for Invasive Plant Regulation recognizes A. pinnata as a harmful invasive plant species that threatens Canadian ecosystems.

Outside of Ontario, other provinces have yet to officially identify Azolla as a potentially damaging species. It is imperative that informative content be spread on the damaging effects of Azolla, to ensure the entirety of Canada can agree on its threat to Canada’s pristine ecosystems.

How You Can Help

In the case of species identification, a useful resource for reporting a sighting is EDDMapS (https://www.eddmaps.org/). This user-friendly resource allows community members to report sightings of invasive species that are then confirmed by trained taxonomists who will identify the species via pictures from community members. This resource is accessible to anyone who wants to know what invasive species may be present in their area.

Remember to never let your pets or other at-home species loose! If you own an aquarium or other house plants, make sure you are consulting proper disposal guidelines for water and living plants. DON’T LET IT LOOSE!

Articles and Research

Brunton, D.F., and H.J. Bickerton. 2018. New records for Eastern Mosquito Fern (Azolla cristata, Salviniaceae) in Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 132(4): 350–359. https://doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v132i4.2033

Evrard, C., & Van Hove, C. 2004. Taxonomy of the American Azolla species (Azollaceae): a critical review. Systematics and Geography of Plants, 301-318.