Watermoss (Salvinia molesta, Salvinia auriculata, Salvinia minima, Salvinia natans)

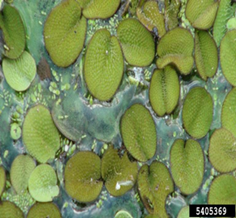

A photo of Giant Salvinia’s leaves (S. molesta)

Courtesy of Robert Videki, Bugwood.org.

A photo of Giant Salvinia’s submerged leaves.

Courtesy of USDA.

Common Names: Water moss, giant salvinia, cariba weed (S. molesta); Eared watermoss, African payal (S. auriculata); Common Salvinia, water spangles (S. minima); floating fern, floating watermoss, floating moss, water butterfly wings (S. natans)

Latin Name: Genus Salvinia; species Salvinia molesta, Salvinia auriculata, Salvinia minima, Salvinia natans

French Common Name: Salvinie

Order: Salviniales

Family: Salviniaceae

Did you know? There are 12 species of Salvinia worldwide, of which 4 species are documented as a threat to invade Canada.

Introduction

Watermosses are a group of ornamental floating aquatic herbs native to Central and South America that are often used in the aquarium trade. Watermoss is made up of 12 different species. Four of these species have been introduced into the United States and are classified as invasive and the same four are also considered a threat to invade Canada. This plant is not currently found in Canada but, due to its close proximity in and around some Great Lake states, the threat of introduction is high. If introduced, watermosses could pose a significant threat to native Canadian plants, and thus entire ecosystems, as it grows rapidly in a variety of conditions and can outcompete native species for space, sun, and nutrients. As it is usually found in the aquarium trade, those interested in aquatic plants should be cognizant of the various invasive versions of watermosses when purchasing a species – or consider buying native species instead.

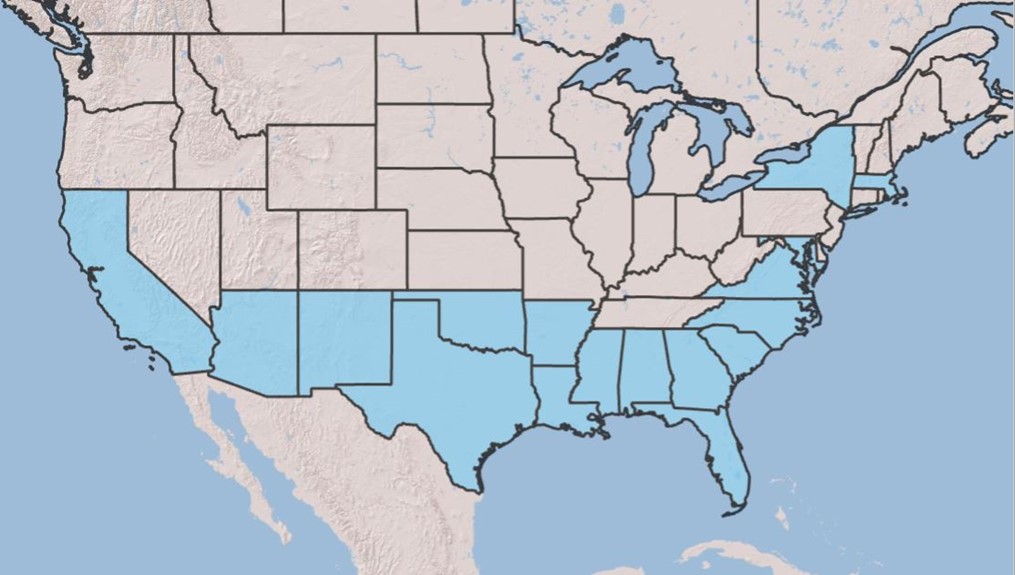

Of the four threatening to invade Canadian waterways, Giant Salvinia (S. molesta) is native to Brazil and was introduced to the United States in the 1990’s. Eared watermoss (S. auriculata) is native to Mexico, all the way down South to Argentina and Chile. It is categorized as both invasive and noxious in the United States. Common Salvinia (Salvinia minima) is native throughout South America and was introduced to the United States between 1920 and 1939. Lastly, floating watermoss (Salvinia natans) has the largest native distribution, with native populations occurring in Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. Floating watermoss has been introduced in the states of New York and Massachusetts.

Description

Watermosses are difficult to distinguish from one another. Each species has a slight variation in their leaves but otherwise have very similar traits.

Leaf Traits

Salvinia molesta

Oval shaped green leaves, less than 1.5cm to 6cm wide, that lay flat on the water’s surface. Leaves have an obvious crease down the middle and fold inward as the plant matures. Leaves occur in whorls of 3 in an opposite orientation, with 2 floating and 1 submerged leaf. Leaves have velvety small hairs that form whisk-like structures when looked at closely.

Submerged leaves are flatter, smaller, and brown in colour.

Salvinia auriculata

Oval shaped green leaves, 8-15 mm wide, that lay flat on the water’s surface. The leaves are densely packed in mature plants. Leaves are in whorls of 3, with 2 leaves above water and 1 submerged. Leaves have round tips with 2 lobes at the tip. Submerged leaves are flat, small, and white in colour.

Salvinia minima

Oval shaped small, bright green leaves, 0.4cm to 2cm in length, that lay flat on the water’s surface. Leaves are in whorls of 3, with 2 leaves above the water and 1 submerged below. Leaves have velvety small hairs that form on the tops of the leaves, shooting straight up vertically from the leaf. Submerged leaves are smaller, flatter, and often brown in colour.

Salvinia natans

Oval shaped small, bright green leaves, 2.5cm long, that lay flat on the water’s surface. Leaves occur in whorls of 3, with 2 above water and 1 submerged below.

The whole plant can be 20cm long, mostly submerged.

Submerged leaves are smaller, flatter, and yellow to brown in colour.

Other Traits

Stem: All watermosses produce submerged leaves on a root-like stem that floats below the water’s surface

Flowers: All watermosses lack flowers

Roots: All watermosses lack true roots as they are free-floating plants

Watermosses are persistent and stubborn plants, which makes them a successful invader. Watermosses can grow outside of their optimal conditions including temperatures, access to light, and nutrient availability (Coetzee & Hill, 2020) – and therefore can successfully grow outside of their native range. Watermosses are distributed through vegetative propagation, which occurs when a fragment of the plant is moved from one area to another and spawns at the new site, growing rapidly (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). Watermosses are therefore very easily propagated as they only require a fragment of the plant for a new plant to reproduced, and accordingly, all parts of the plant must be controlled so as not to spread. Distribution of watermosses can also occur due to water currents or by physical contact, such as by swimmers or boats. Once situated at a new site, watermoss populations can double their population size in just three days when under favourable conditions (Coetzee & Hill, 2020).

Watermosses undergo an exponential growth and has three growth stages: initial plant invasion and growth, secondary growth stage, and tertiary growth stage (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). Watermosses are more difficult to visually detect during their earlier growth stages, as they mostly grow in small populations under the water’s surface, but as they mature, will reach the water’s surface and form dense mats of vegetation spanning the surface (Coetzee & Hill, 2020).

Watermosses will fail to grow under -4°C or over 40°C but are hardy and will still grow under non-optimal conditions within this temperature range (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). When watermosses experience winter temperatures, plants will die off. However, plants have also been observed as re-sprouting in spring temperatures when waters warm, from seemingly dead plants (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). It is therefore very important to keep in mind that watermosses can still very much grow and persist in Canada’s colder climate.

Watermosses tend to grow in warm (30°C), high sunlight, and high nutrient waters, similar to their native range (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). Watermosses are an aquatic freshwater plant, and therefore only occur in freshwater ecosystems. The optimal growth of watermosses occurs in minimal water current conditions, but due to the plant’s hardiness, it has been found in still waters, canals, rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and swamps. Optimally, watermosses grow in conditions that are high in sunlight access and nutrient availability but have been observed to persist in areas lacking high levels of sunlight and nutrients (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). Water temperatures also have an optimal temperature of 30°C for watermosses to grow the most rapidly, but this plant has been observed growing in temperatures between -4°C and 40°C (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). This plant does not overwinter but has been observed sprouting from seemingly dead populations after the winter, showing its persistence and hardiness to less than optimal temperature conditions (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). Due to watermosses not having a root system, they can therefore grow in a variety of soil and substrate conditions.

Watermosses are native to throughout mainly South America, with one species native throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa as well. Salvinia has been introduced to the southern United States and along the East Coast, including New York and Massachusetts. Globally, watermosses have been found in parts of Africa, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Papua New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Cuba, Trinidad, Borneo, Columbia, Guyana, Philippines, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Watermosses have been distributed globally through commercial trade as an aquarium and ornamental plant. In fact, Salvinia species are easy to find on the Canadian market. This accessibility speaks volumes for the necessary outreach and education that is needed around this plant and how it threatens our ecosystems.

Watermosses are typically distributed into the wild through either accidental or intentional release from aquariums and ornamental ponds. Once in the wild, Salvinia is distributed by water currents and by physical contact. Fragments of watermosses can get stuck to swimmers, boats, and even wildlife, and deposited elsewhere, creating a new population.

It important to clean, drain, and dry your boats after exiting a waterbody, as to not transfer numerous invasive or pest species from region to region. It’s also important to remember: Don’t Let It Loose!

Ecological Impacts:

Due to the watermosses abilities to grow in dense patches at the water’s surface, this blocks out sunlight to any native species dwelling below. Watermosses also use up valuable and sometimes scarce nutrients in the waterbody, denying nutrients for native organisms. The blocking of sunlight and use of nutrients often decreases plant, invertebrate, and wildlife diversity. Losing biodiversity in an ecosystem often leads to low oxygen levels, which can cause the system to uninhabitable for long periods of time. The alteration of water chemistry can be irreversible and often has deeper impacts on nearby ecosystems.

Social and Economic Impacts:

The dense growth of watermosses can impact the recreational use of waterbodies, such as swimming and boating. Watermosses have the potential to become entangled around motors and paddles. This can in turn decrease waterfront property values. Watermosses can also clog irrigation channels which may cause flooding or drought in some areas. Due to a decrease in biodiversity, watermosses cause disruption in aquacultural cultivation. It has been known to disrupt the cultivation of rice, catfish, and crawfish, but has the potential to affect more species.

The Ontario government has proposed watermosses to be prohibited under the Invasive Species Act (New invasive species proposed for regulation under the Invasive Species Act | ontario.ca). Prohibited species are illegal to bring into the province, which includes the possession, sale, and propagation of the species within or into the province.

The prevention of species introduction is much easier and cost-effective than controlling a species once it is established. Thus, it is of high importance that watermosses are not introduced to Canada, as they pose a significant risk to Canada’s native species and would cause significant economic impacts for their removal and management.

The United States have previously found the introduction of the salvinia weevil, Cyrtobagous salviniae, has been successful in managing Salvinia populations as a biological control agent (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). This weevil feeds on the Salvinia plants but may pose a new threat as it is a non-native insect introduced to areas where Salvinia is introduced. The salvinia weevil is native to Brazil, and therefore should not be considered an ideal management tactic. However, chemical control of Salvinia via herbicide has also caused significant struggle, as the plant is persistent in growth even after treatment (Coetzee & Hill, 2020). Herbicide is also a very costly management option for invasive plants and can have detrimental effects on any non-target native plant species nearby the chemical treatment. Given the persistence and difficulty to manage watermosses, it is imperative that they not be introduced to Canada’s delicate and economically significant fresh waterways.

Watermosses are difficult to detect in their initial growth stage, due to its small size and its main growth occurring underwater, however, during its secondary and tertiary stages of growth, watermosses reach the water’s surface and forms dense mats that can span meters wide and up to one meter thick. The main sign of watermosses present is the death of native plants. Due to the rapid growth and size of watermosses, the plants both block out sunlight to native aquatic plants and take up valuable nutrients that native plants require. This decrease in plant biodiversity in turn will have whole effects on the ecosystem, causing decreases in insect, fishes, and wildlife diversity. Reptiles and amphibians are commonly used as indicator species, as they are most susceptible to environmental changes. Therefore, the most obvious sign of watermosses growing is a decrease in native plant diversity and a decrease in the nearby wildlife populations.

Outside of Ontario’s proposal for watermosses to be a prohibited plant under the Invasive Species Act, it is important to determine how other Canadian provinces are handling the threat of this plant.

Currently, Alberta has declared Giant Salvinia (Salvinia molesta) as prohibited under the Fisheries (Alberta) Act. Quebec’s Ministere de l’Environnement categorizes Salvinia as a “Species not listed in Quebec” but does recognize its threat.

Other Canadian territories and provinces have yet to make legal recognition of watermosses. Ontario is arguably the most threatened province by this plant, as its distribution is found in the connected and close-by states of New York and Massachusetts.

How You Can Help

In the case of species identification, a useful resource for reporting a sighting is EDDMapS (https://www.eddmaps.org/). This user-friendly resource allows community members to report sightings of invasive species that are then confirmed by trained taxonomists who will identify the species via pictures from community members. This resource is accessible to anyone who wants to know what invasive species may be present in their area.

Remember to never let your pets or other at-home species loose! If you own an aquarium or other house plants, make sure you are consulting proper disposal guidelines for water and living plants. DON’T LET IT LOOSE!

Articles and Research

Coetzee, J. A., & Hill, M. P. (2020). Salvinia molesta D. Mitch.(Salviniaceae): impact and control. CABI Reviews, (2020).

Resources

Ontario Invasive Plant Council: https://www.ontarioinvasiveplants.ca/

Science Direct: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/salvinia

Biology and Control of Aquatic Plants, 2.13 Giant and Common Salvinia: https://aquatics.org/bmpchapters/2.13%20Giant%20and%20Common%20Salvinia.pdf

Centre for Aquatic and Invasive Plants: https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/salvinia-minima/

United States Geological Survey: https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=298

Alberta Invasive Species Council: https://abinvasives.ca/fact-sheet/giant-salvinia/

Ministere de l’Environnement: https://www.environnement.gouv.qc.ca/eau/paee/fiches/salvinia.pdf

Global Biodiversity Information Facility: https://www.gbif.org/species/5274863

Global Invasive Species Database: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=569

CABI Digital Library: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.48447

Further Reading

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Ecological-Risk-Screening-Summary-Giant-Salvinia.pdf

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Ecological-Risk-Screening-Summary-Floating-Watermoss.pdf

Government of Ontario proposed prohibited invasive species: New invasive species proposed for regulation under the Invasive Species Act | ontario.ca